Stones & Measures

Applying Theory of Continuous Quantity

The Experiment

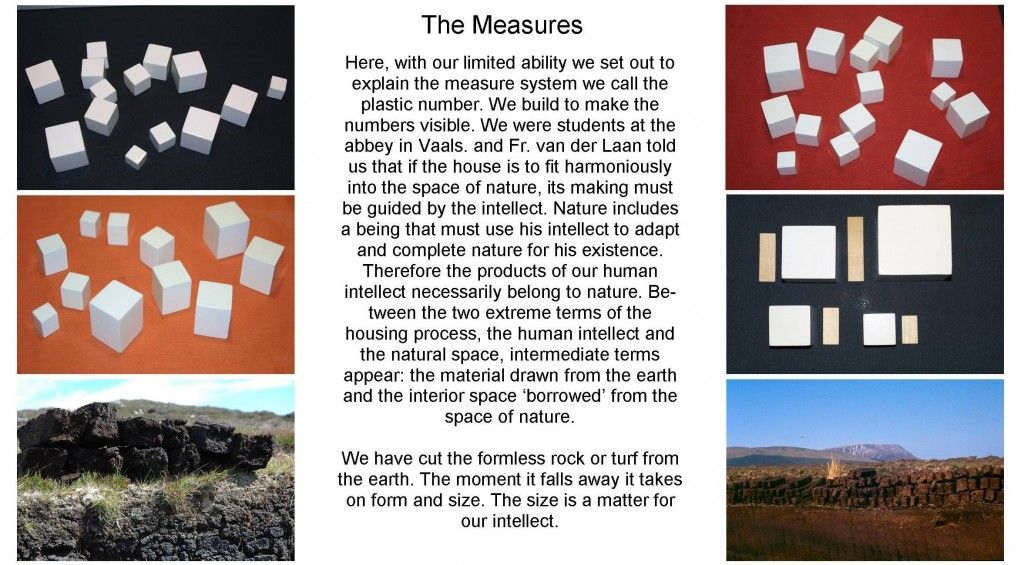

To test our ability or desire to impose order on continuous quantity, we gathered a random selection of 300 stones of various sizes. We threw them in a heap on the sand.

No sooner than this was done, another group of the largest stones appeared. We removed these and placed them along the side of the bunch. We repeated the exercise until the whole heap was sorted into seven bundles.

We understand this to be an expression of our intellect, which is to simplify what is beyond our comprehension. We reduced the bundle to 36 carefully graded stones from small to large. We worked the test again.

A pattern seemed to emerge that suggested the limits of people’s capacity to deal with continuous quantity. Continuous quantity as presented to us in nature was naturally broken down into 7 sizes: smallest, very small, small, medium, large, larger, largest.

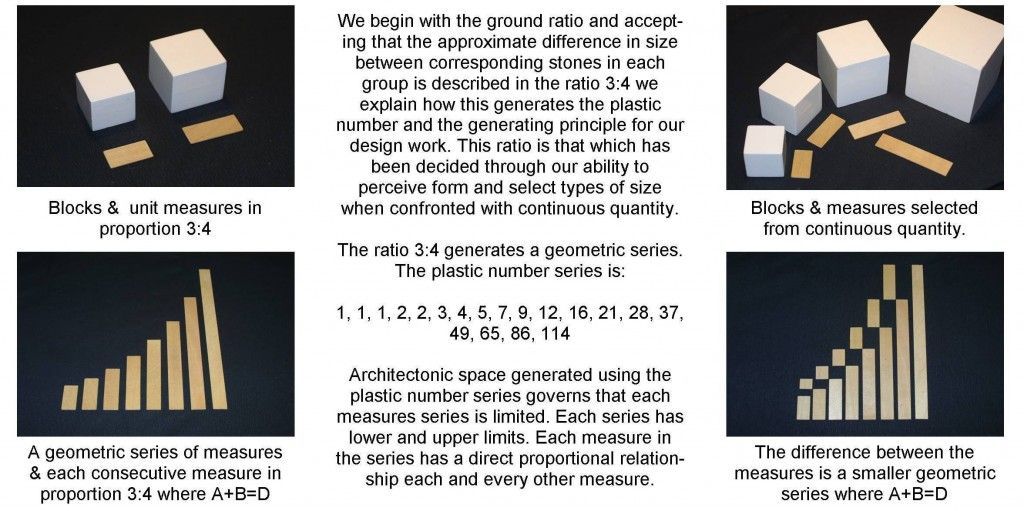

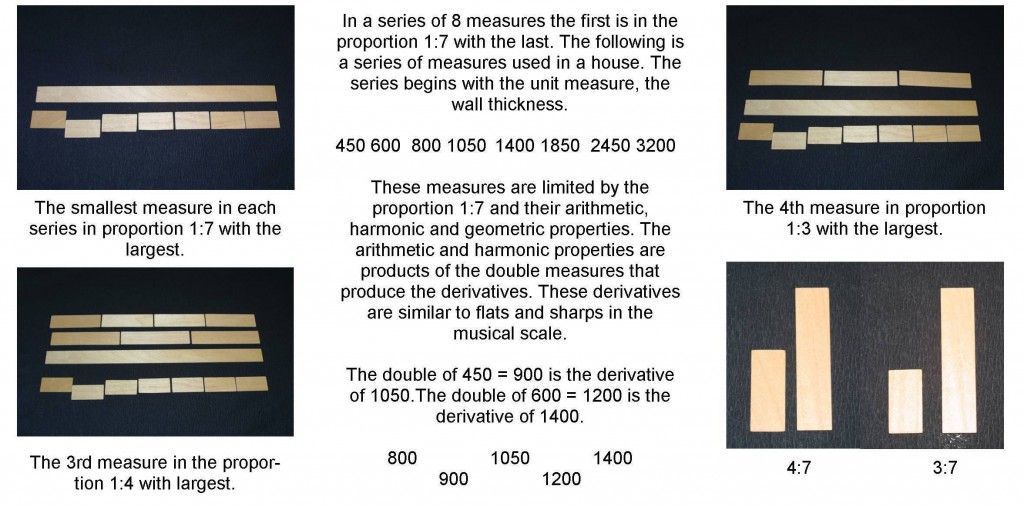

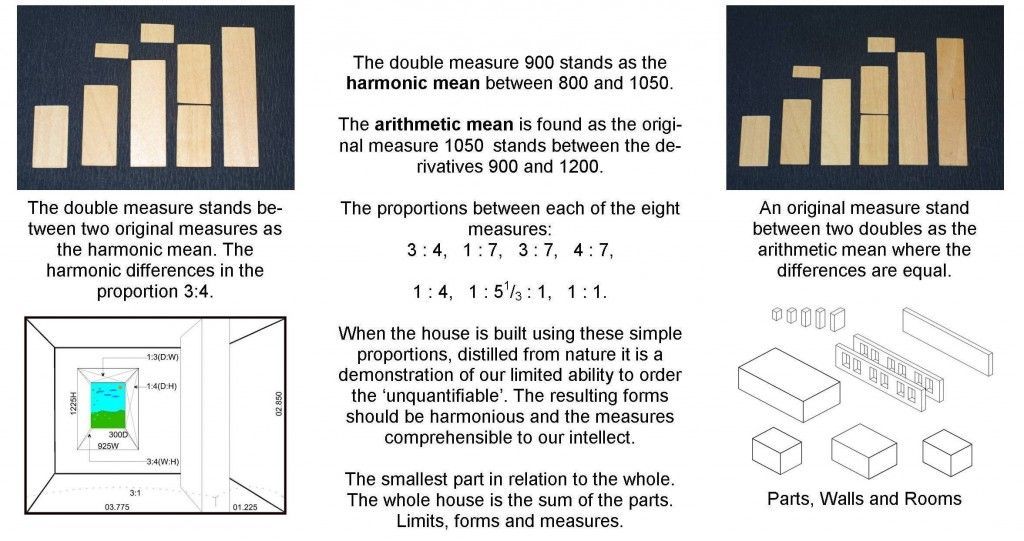

The original experiments undertaken by the Benedictine monks showed that the difference in size between corresponding stones in each group was in the ratio 3:4.

The ratio 3:4 produces a geometric series very similar to the Fibonacci series. This new series, christened the ‘plastic number’ is slower and described as A+B=D. The reason we think it is slower is due to the 3rd dimension in our experimental materials. The Fibonacci or Golden series (A+B=C) is based on the division of a 2D shape.

Music & Number

Most western music is written in one key. Each key has seven notes. It is universal and the limited number of notes doesn’t restrict creativity. The Greeks, Palladio, and Corbusier knew the important of number and its relationship to harmony. Palladio set out the rooms in his villas using measures and proportions derived from a musical scale.

Architecture is like music in that it should bring joy and delight or be sombre and sad, depend on how the building is to be used. Regardless of the mood required, it should have melody and harmony, order and rhythm, proportion and scale. Then, it is peaceful and bright.